Shifting the Narrative – a New Approach to Leadership

Irum Ahsan is a trained lawyer and Advisor at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Manila, Philippines. The Pakistani-born is a core member of Law and Policy reform team of the bank. Her areas of expertise are environmental and climate justice and gender equality. She took part in the Transforming Leadership Lab.

“You don’t have to wait to be appointed as a leader. The impact of your work makes you a leader.”

Irum Ahsan

In Pakistan, there is an old custom whereby girls are handed over to the respective aggrieved family as "compensation" for the offences committed by their male family members. We, a team of lawyers, had petitioned the Supreme Court against this custom. Several women were released as a result, including an eighty-year-old woman who, as a nine-year-old, was given by the men in her family as compensation to the family of the boy they had murdered. The old woman kissed her lawyer on the forehead in gratitude for her release. This picture touched me so much that I decided that I need to do more than just a corporate law practice. That was in 2004.

“Why should we be focusing on gender-based violence?”

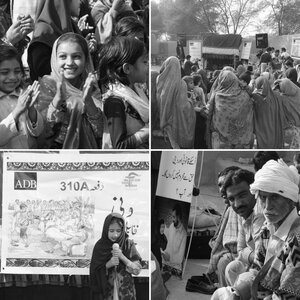

At the Asian Development Bank (ADB), under the legal department’s Law and policy Reform Program, I together with my comrades started a legal literacy for women project. At first, to get the project approved, I had to show the linkage between economic empowerment and development of women and how it is hampered by gender based violence. I provided a rationale that if ADB, as a development bank focuses on infrastructure, building roads and bridges but the women of these member countries don’t feel secure enough to use these facilities then by all means the ADB will only be able to contribute to developing less than 50% of the Asian Pacific members, that are men.

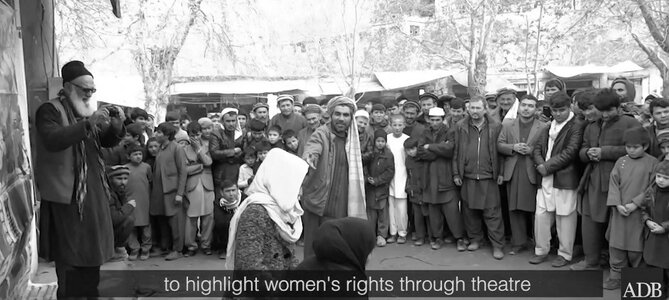

The project, implementation started in 2016 and targets both male and female justice sector stakeholders. We decided to work in Afghanistan and Pakistan because gender-based violence is widespread in these countries. We had two objectives: To provide women with better access to justice through the training and awareness-raising of judges, prosecutors, magistrates and religious scholars, and to raise social awareness within the communities of gender-based violence.

You don’t need to have a leadership role to be a leader

At the same time, I took part in the Transforming Leadership: Women, Men, Power and Potential: A Leadership and Innovation Lab. This Lab has completely changed my perspective and gave me tremendous confidence to go back to my project. Before the lab, my definition of leadership was that I needed to have a specific position to be a leader and to be able to bring any effective change. The lab actually taught me that leadership means that you are able to shift the narrative, the perspective, even if you don’t have a “leading” position.

In this framework I also realized that if I am only able to change the mindset of five people in a room of 30 that is good enough. These minds are going to go out and change further minds. So that is a success and that is leadership. I don’t have to prove a point or change the whole world in the course of one project, I should just change the world for one person. This is the approach I picked up from the lab. On a personal level I really feel like a leader now and I present myself as a leader and as a result, I have been accepted and seen as a leader. In terms of the project I am running I learned that I can share my knowledge with so many more people.

Back to my project I decided to start small. I began to work with one province in Pakistan. Pakistan is a huge country with four provinces, and gender issues are multi-faced. I knew with the resources I had at hand it would be impossible to reach all provinces. Gender work is not only about reforms laws and practices. Gender work is also mindset change. I chose the province in which I already knew the Chief of Justice who had a gender sensitive heart. Moreover, this province was also considered the epicenter of gender-based violence in the country. So, the right province and the right leadership, that was the strategy I chose.

When I met the Chief of Justice, he said: “Look, I have many issues related to gender: violence against children, violence against LGBTI, violence against women, then also institutional problems within the judiciary.” He gave me a wish list with probably 20 things, but I knew we couldn’t address all issues in one go. I said: “Let me focus on gender-based violence because that is your prime issue relating to access to justice. And once you fix access to justice this will automatically impact on other issues that your courts are facing.”

The trainings – just the beginning

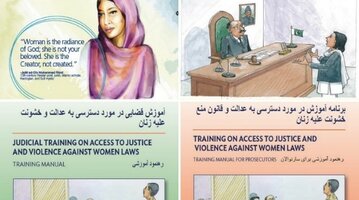

First, the Chief Justice said: “I will give you access to my judiciary only under one condition: that you will not bring and impose any imported western ideas. Pakistan is a very particular country, it has customs, cultures and norms and it has its own laws. Your training has to be customized to the needs of our country.” And I agreed.

We reviewed customs, religious beliefs, societal norms, in addition to more than 50 laws of the country and compared them with international laws and best practices. We also conducted thorough needs assessment by meeting with more than 100 judges and prosecutors to assess what their challenges were: are there issues with their understanding of laws, both national and religious? Are they confused with customs? Is there an issue with societal pressures and mindsets? We identified those challenges, then prepared a comprehensive needs-based training completely customized to Pakistan. We ended up training more than 300 judges in one province. The judges reported to the Chief of Justice saying that they always thought that gender-based crimes are just one of many regular crimes and nothing special. But after the training they realized that it is a very difficult and technically complex field and that they really needed tools to address this issue. One of the tools, that they identified was a specialized court.

"First, the Chief Justice said: 'I will give you access to my judiciary only under one condition: that you will not bring and impose any imported western ideas. Pakistan is a very particular country, it has customs, cultures and norms and it has its own laws. Your training has to be customized to the needs of our country.' And I agreed."

Irum Ahsan

The Model GBV Court

The Chief of Justice said: “Brilliant. I need a model court in my province” – that took us by surprise, but we were ready to respond once we got our mandate. We were given a room in a regular courthouse to adjust it to the needs of privacy of the women and GBV victims. Together with the technical workers like carpenters, we restructured the court room and added some required infrastructure including: (i) bright and clean pain; (ii) screen and chair for the victim/witness so that women/victims could sit behind the screen not having to face her rapist or perpetrator again in the court; (iii) moved the lawyer’s table away from the judge and the witness box so that judges, witnesses and victims could get space and are not feel harassed during the trial; (iv) We provided electronic evidence facilities in another room if a woman/victim could not come to court; (v) a second room for children who come for evidence or simply accompany the mother; (vi), and a female facilitator who can help and guide the woman at court.

To compliment the infrastructural changes, we also drafted court procedure guidelines and practice notes to guide the judges in GBV related court hearings, like what questions to ask, what questions not to ask. We also provided practical skills learning sessions using role-play methodology during our trainings so that judges are equipped with better understanding of laws, procedures and skills. This is what happened with a small intervention. We had this model court put together literally within a week’s time.

Small Intervention – Huge Impact

After a year during which we kept on supporting the court and helping the judges we realized that the conviction rate of rape cases went up from 2% in 2016 to almost 16% in 2018. Our small intervention had a huge impact. But this was only the beginning.

We went to the Chief of Justice of the Supreme Court and National Judicial Policy Committee and showed them our results and what we had achieved so far in this one province. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was very impressed: “I want this court in each district of my country” (around 116 districts). “I want the Asian Development Bank to provide training to at least one judge from each district”, he said. We felt so proud of our work especially because it was based on results and impacts. Pakistan judiciary itself took ownership and decided to replicate results nation-wide.

Then we went back with a new mandate, and I requested ADB to supplement funding. The ADB was ready to supplement because we produced impacts, results and success… Back to Pakistan we provided extra training to all these judges and prosecutors. We handled the soft component of this initiative through customized training and customized court procedures and left the infrastructural part of the courts to the judiciary itself.

All this happened after my lab participation. I believed in my small interventions which I wasn’t very much sure about in the beginning but after the lab I went back filed with new energy and confidence. In 2018 I was nominated for the most innovative lawyer award . When I received the award, I explained my personal lessons learned from the lab: We can achieve huge impacts by thinking small. If you start small, you get focused work and targeted interventions which can result in huge impacts. Finally, a further insight was: You don’t have to wait to be appointed as a leader. If you do your job as a team member well, you are already a leader. The impact of your work makes you a leader.

Contributing to the global goals

Thanks for the photos

Use of photos by courtesy of ADB.